After reading my book Storm Surge, Capt. Mike Forsyth sent me an email, in which he included the story of his experience in Sandy. It’s a good story, and so with his permission, I am putting it up as a guest post here. What follows is Capt. Mike’s self-introduction, followed by his story.

–Adam

I was born and raised on Staten Island, spent two weeks of most childhood summers on Long Beach Island, NJ, and as an eight-year-old child was brought by my parents to LBI to see a navy destroyer put up on the beach by the Ash Wednesday Storm. I am a tugboat captain, and work for a New York-based tug and oil barge company. If, as “W” said, America is addicted to oil, I am a mule. However, I have been intellectually convinced of the reality of climate change since the mid-1990’s. This was reinforced by a conversation with a meteorologist about a destructive line of storms that came through upstate New York, where I now live, on July 14th, 1995. The reality was driven home, quite literally, when a similar line of storms did $45,000 damage to my home in a few seconds on Labor Day 1998. I support candidates, donate money, keep myself informed, try to reduce my own carbon footprint, and speak out on the issue when the occasion arises.

My Hurricane Sandy Story

© 2015 Capt. Mike Forsyth

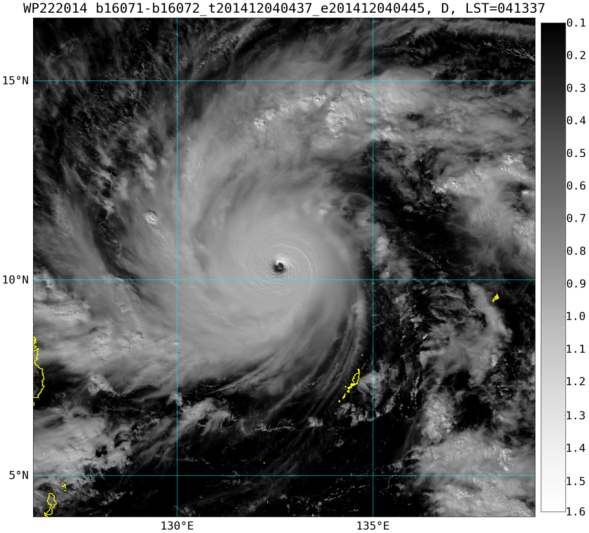

In October of 2012, I was captain of the tug Stephen-Scott, engaged in moving Reinauer Transportation Company’s oil barges in the Northeast. I worked on another Reinauer tug on the Gulf of Mexico during the previous year’s hurricane season and spent a good bit of time following forecasts and tracking storms on charts. On Wednesday morning, October 24th, I drove to Reinauer’s dockyard, at Erie Basin in the Red Hook section of Brooklyn, parked my car and started my two week tour of duty. Almost immediately, I started paying attention to Sandy while she was still in the Caribbean.

On Saturday morning, October 26th, I received orders to take a 60,000 barrel barge loaded with diesel fuel from a New Jersey refinery to Newburgh, New York, about fifty-five miles up the Hudson. By that time, it appeared likely that the storm would impact New York Harbor. The Hudson River at Newburgh is within the US Coast Guard Captain Of The Port (COTP) of New York zone, and the USCG had issued a storm-related notice requiring commercial vessels staying in the COTP NY zone to file a “remain in port” plan. My plan was to depart with the barge that evening as ordered, and arrive early Sunday morning at the oil terminal in Newburgh, discharge the cargo of 2.5 million gallons of diesel fuel, then anchor in the Hudson River off Newburgh until New York Harbor was re-opened to navigation. The plan was received and approved by the COTP.

The prediction for the storm surge was then four to eight feet. The paved parking area at Erie Basin is at dock level, probably seven or eight feet above the high water level. I expected that there would be some water running across the pavement or possibly a little ponding, if the storm hit at other than low tide. My Honda Element has good ground clearance, but that would not be enough. Before my boat left Erie Basin that Saturday, I drove to the Pep Boys auto parts store in Park Slope and bought a couple of oil-change ramps. Back at Erie Basin, I put a staggered stack of 2×12″ lumber about 8 inches high in front of each rear wheel, and put the oil change ramps in front of the front wheels, and drove ahead and up. I figured that would keep salt water out of the engine compartment, and maybe keep the brakes and suspension out of the water.

Our barge discharged its cargo on Sunday, October 28th, and we dropped anchor in the Hudson between Newburgh and Beacon at 8:50 that evening. I was following the forecasts, and had the feeling that my precautions with my car were pitiably, laughably, inadequate. An 8 to 11 foot surge would float the car off the blocks, and fill it with harbor water. Monday morning I checked the forecast, and called my insurance agent to make sure that my comprehensive insurance included flood damage. She confirmed that, and gave me the telephone number for claims, which I told her I expected to use later that week. There was absolutely nothing more I could do.

Within an hour, I got a phone call from Chris, the captain of the tug Jill Reinauer. He told me that his boat and the Kristy Ann Reinauer were at Erie Basin and their crews were moving all the cars they could to higher ground. I told him where my spare key was. I told the other tug and barge crewmembers to call the Jill or the Kristy, so that their cars might be saved. I woke up my first mate, Davey, and asked about his spare key. He told me that his new car had a “smart” key, so smart that a new one cost about two hundred dollars, so he hadn’t had a spare made. Too smart for its own good, his car was a total loss by nightfall. Someone sent him a cell phone video of his car, doors-deep in water with the lights flashing and windows going up and down while the salt water shorted out the electrical connections.

Sunday night and Monday, several other tug and barge units had joined us at anchor off Newburgh. Monday afternoon and evening, the wind and rain came through, fierce, but a pale shadow of what had befallen the coast. Like the other captains and mates, we kept a close watch on GPS chart plotters and radar, in case the wind and current caused a vessel to drag anchor. I also watched our depth sounder, and compared the readings to the charted depth and the predicted normal tidal changes. The depth under the keel reached the predicted maximum early, and continued to increase. On the electronic display of our depth sounder, I could see the storm surge from Sandy pass under our keel, several feet above the maximum predicted by the moon and the sun, while a powerful current carried this surge of water upriver.

On the chart plotter, a neat circle, centered on the spot where our anchor had dropped, circumscribed what should have been our range of motion in any direction. The “own ship” icon on the chart plotter crept slightly closer to the edge of the circle. I started the twin 1,700 horsepower engines and put the propellers in gear at low speed to try to oppose the force of the surge. The radar range to the next vessel anchored up river began to decrease, and it was clear that our anchor was dragging. I have dragged anchor numerous times on the Hudson. However, that usually happens when gravity carries the run-off from heavy rains or snow-melt down from the hills and mountains, adding fresh water to the ebb tidal flow, and usually with a northwesterly gale blowing as well. I have never, before or since, dragged anchor on the flood current of incoming ocean water in the Hudson. We picked up the anchor, stemmed the tide under power, and when the surge had passed, we re-anchored, and remained there until November 1st. We moved down to the section of river off the Upper West Side of Manhattan, and anchored for another two days, until portions of New York Harbor were re-opened to limited navigation.

During this time at anchor, I received welcome news that my car had been moved from Erie Basin to the roof of the parking garage of the nearby Gowanus branch of The Home Depot, and then returned to Erie Basin, none the worse for the experience. Some cars were moved from Erie Basin, but parked in the lower level of the Red Hook Ikea parking garage. They did not fare as well, since all basements and first floors in Red Hook were inundated by the surge. About forty cars were saved. Returning to Erie Basin on November 4th, I counted twenty cars and pickup trucks belonging to fellow employees which obviously had not been moved out of harm’s way. I was puzzled by big dents in the roofs of some of them. Then I saw some anchor buoys, yellow-painted hollow steel balls about four feet in diameter which are used to mark the location of dredge anchors. These had obviously come from the far side of Erie Basin, and were on the pavement by a chain link fence which is the boundary of the employee parking area. They apparently floated across the basin, blown by the wind, until they came up against the fence, floating above the parked cars. The dents in the roofs were made by the steel buoys, bobbing up and down on waves and pounding on the roofs. The oil change ramps would not have done the job.

The waterfront was dramatically changed by Sandy, with destruction and large mis-placed items all around. Most striking for several days after the harbor re-opened was the absence of lights. For decades, New York mariners have been complaining about light pollution, more numerous and brighter lights on shore, which impair night vision and can make buoys and navigational lights difficult to see. The power was out at most waterfront facilities, including oil docks, for a long time after the storm. Here and there were construction lights from a portable generator, or an isolated dock which had power restored, but mostly we had a dark shoreline for a couple of weeks. With most of the oil terminals in the metropolitan area out of commission, I reflected that the 2.5 million gallons of diesel fuel which we delivered probably was put to good use in the immediate recovery from the storm, since Newburgh had some of the closest oil terminals to New York which were still in operation.

At the end of my two weeks, I was able to drive home in my own car, thanks to efforts in the teeth of the storm by the crews of two tugboats, and to the people at the Gowanus Home Depot. The tugboatmen did something above and beyond the call of duty or any job description, bordering on heroic. Boatmen don’t have to do these things, but no one in the business is surprised when they do. It is almost expected. (The first four Apostles were boatmen, not farmers or shopkeepers or divinity students, and the choice was probably well-considered.) However, the folks at Home Depot could have easily blathered some corporate line about liability, and closed their doors to those seeking shelter from the storm. Instead, they did a great thing for people in their neighborhood, including Erie Basin in Red Hook. That deserved some recognition.

I had three dozen custom tee shirts made. On them was imprinted the legend, “Hurricane Sandy – October 29, 2012 – Heroes of Erie Basin” at the top, followed by drawings of the two tugboats done by a professional artist, and at the bottom, “The Crews of the Tugs Jill Reinauer and Kristy Ann Reinauer, and Home Depot, Gowanus, Brooklyn”. On my next crew change, I went to the Home Depot, saw the assistant manager, and gave him half the tee shirts to distribute to those deserving however he saw fit. He was overwhelmed. He had a co-worker hold a shirt while he took a cell phone photo and sent it to his manager at home. I gave the other half to the tugboat crews who moved the cars in the wind, rain and rising water. A few months later, I started a kitchen remodeling project and ordered $2,400 worth of cabinets from Home Depot, which, pre-Sandy, I would have bought somewhere else.