This post contains some remarks on the tropical cyclone, likely to soon become Cyclone Nisarga, currently forming over the southeast Arabian Sea. This storm poses a risk to the northwest coast of India, including the city of Mumbai. While it might well turn out to be a minor event, there is also some possibility it could be bad enough to cause a major disaster. Landfall is probably 3-4 days away; official cyclone forecasts usually give five days’ lead time, but haven’t been issued yet because the storm hasn’t officially formed yet. In this situation, where a storm forms a short time before landfall, it is challenging to communicate the nature of the risk. This post is an attempt to help do that.

A disclaimer: I am not issuing a forecast. The India Meteorological Department is the authoritative source of weather forecasts for India (and in the case of tropical cyclones, the entire North Indian Ocean basin), and their forecasts are state-of-the-art. I am just an academic and private citizen offering some interpretation. My comments are based on publicly available observations and numerical model predictions. I am writing this late in the evening in New York on May 31, 2020, which is early in the morning on June 1 in India. The information will become dated rapidly.

The latest IMD Tropical Weather Outlook is available here. As I write, it discusses two storms; the first is over far the western Arabian Sea, around the Oman and Yemen coasts. The second, forming over the southeast Arabian Sea, has not officially formed yet (meaning its winds have not yet reached the threshold necessary to qualify as a cyclone), but once it does, it will be named Nisarga. The IMD Outlook currently predicts of this storm that “IT IS VERY LIKELY TO CONCENTRATE INTO A DEPRESSION OVER EASTCENTRAL AND ADJOINING SOUTHEAST ARABIAN SEA DURING NEXT 12 HOURS AND A CYCLONIC STORM DURING THE SUBSEQUENT 23 HOURS. IT IS LIKELY TO REACH NORTH MAHARASHTRA AND GUJARAT COASTS BY 3RD JUNE.” By this point, if this forecast is correct, the storm will have been formally given its name. The category “Cyclonic Storm” is a storm of relatively mild intensity (34-47 knots, 63-88 km/hour), equivalent to the US “Tropical Storm”. Such storms generally do not produce tremendous wind or storm surge damage (though they can still produce enough rain to cause heavy flooding).

The different numerical weather prediction models (run by different government agencies around the world) have been predicting a disturbance to form around this time for some days, but have come to agree in the last day or two that a storm of some intensity will form and make landfall somewhere on the northwest coast of India, either Gujarat or Maharashtra. Below (Figure 1) is a map of predictions of the storm center’s track from different models as of 12 UTC today.

Figure 1: Track predictions from an ensemble of different numerical weather prediction models. The different colors indicate different models, whose names are abbreviated in the legend at upper right. “Invest 93” is the name for this storm given by the U.S. Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Plot obtained here from the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

The models disagree not only on the exact landfall point, but also on the intensity of the storms at landfall. In many of the models, the storm remains relatively weak. But in a few of them, it becomes quite strong.

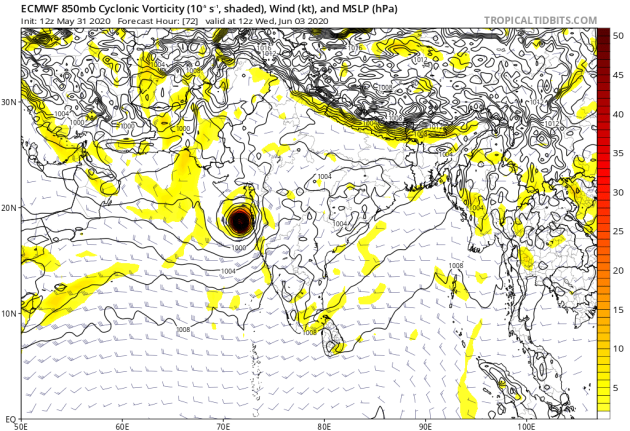

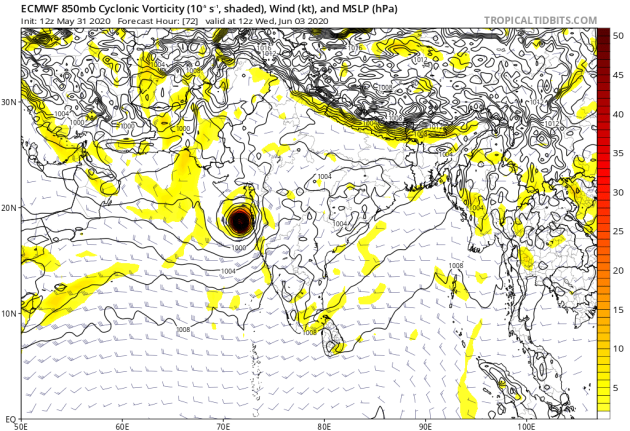

In the ECMWF model – arguably the best in the world (though that doesn’t make it the most correct on every occasion) – the storm becomes quite powerful and makes landfall just north of Mumbai. Below (Figure 2) is a map of the latest model run available as I write, showing the prediction for 12 UTC on Wednesday (5:30 PM IST); the storm is headed northeastward so that it comes ashore just north of Mumbai, likely exposing the city to the stronger winds on the right side of the storm and attendant storm surge. This scenario would be quite bad for the city, as it could generate a large storm surge and consequent flooding, especially if it occurs at high tide.

Figure 2. Plot of surface pressure (contours) and winds (barbs, kt) and vorticity (a measure of the winds’ rotation) at 850 hPa, around 1.5 km above the earth’s surface, from the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting (ECMWF) model. The model run was initialized on May 31, 2020 at 12 UTC, and the prediction shown is for June 3, 2020 at 12 UTC (530 IST).

The ECMWF could well be wrong, but there’s no way to be certain at this moment. So, as far as we know now, there is at least some risk of a substantial disaster in Mumbai, a city with a metropolitan area of 20 million, exposed to the sea, where an event like this has not occurred at least since the late 19th century (perhaps centuries earlier). There have been major floods in recent years, 2005 especially, also 2017 and 2019, caused by rain from monsoon weather systems. These were not cyclones. A cyclone could be different, due to the possibility that it could produce very high winds and storm surge. It could possibly be even worse than these events.

In the models, landfall occurs on Wednesday or Thursday local time, three or four days from now as I write this. Normally – in India as in most of the world – official forecasts of a tropical cyclone’s track and intensity are issued for a period from now to five days into the future. However, these official forecasts don’t start being issued until the storm has officially formed and been given a name. So if a storm makes landfall less than 5 days after it forms, there is less advance notice than their normally would be. This is what is happening in this case.

The IMD’s Tropical Weather Outlooks, if one reads the text, have been discussing the possibility that a storm could form for a couple of days, and have been giving broad, general statements about its future path, as I quoted above. But no quantitative, specific forecasts of the storm’s track or intensity have been issued yet, because it hasn’t yet formed. One could make such forecasts based on the models, and particularly now, that might be a good idea, but that isn’t the practice. (In the US, the National Hurricane Center started a couple of years ago to issue Hurricane Warnings in such cases, where a Hurricane is expected to form and make landfall within a couple of days, if it poses a significant threat to land. But that is a new practice, not yet adopted worldwide.)

It could well be that the storm will end up being weak, or will only affect areas less populated than Mumbai, or both. But because Mumbai is so exposed and so vulnerable, even a small chance of a major tropical cyclone landfall there is worth being aware of, as far ahead as possible. There does seem to be, at present, such a chance.